Founded in 1934, Bombay Talkies was co-owned by Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani. He was associated with a number of movies, including Goddess (1922), The Light of Asia (1925), Shiraz (1928), A Throw of Dice (1929) and Karma (1933). The studio produced 40 films over 20 years and was considered as the most technically advanced Indian studio of its time.

The story begins, as many good stories do, in an attic. That’s where 30-something Australian Peter Dietze discovered a black-and-white photograph of a handsome young Indian man. He asked his mother about the picture and was told it was of Himanshu Rai, pioneering founder of Bombay Talkies, legend of the early years of Hindi cinema. And also, Peter’s grandfather.

His mother had never mentioned Himanshu to him, nor even hinted that he had any sort of Indian ancestry. For the Melbourne businessman, this was a defining moment of his life. “When I saw the photo, it struck me that I looked a bit like him. I have his nose,” says Peter, over a phone call from Australia. “It was extraordinary. I tried to find out about my Indian ancestry. I photocopied the pages on Bombay Talkies from a book I had on Indian cinema.”

His mother had never mentioned Himanshu to him, nor even hinted that he had any sort of Indian ancestry. For the Melbourne businessman, this was a defining moment of his life. “When I saw the photo, it struck me that I looked a bit like him. I have his nose,” says Peter, over a phone call from Australia. “It was extraordinary. I tried to find out about my Indian ancestry. I photocopied the pages on Bombay Talkies from a book I had on Indian cinema.”

In India, Himanshu Rai is known as the husband of the stunning Devika Rani, so the news of an unknown secret wife is something of a revelation.

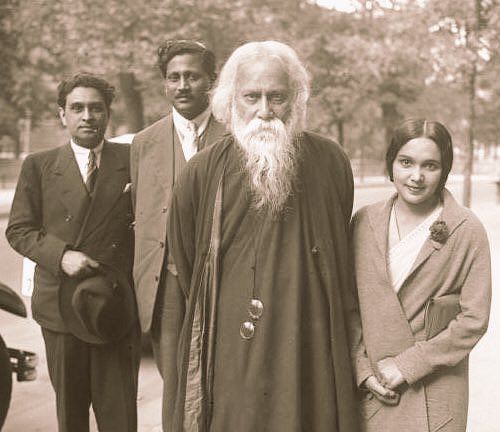

Rai with his first wife, Mary Hainlin

Peter’s discovery happened more than two decades ago. Today, he is the owner of an enormous collection of Bombay Talkies memorabilia covering the 1920s and 1930s – one of the most exhaustive film archives in the world. And in the last six months Australian curator Fiona Trigg has trawled through over 3,000 photographs, posters, letters, telegrams, screenplays, invitations and bills to mount a major exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne, called simply Bombay Talkies.

How all this came about is a film-worthy story in itself.

Himanshu Rai is one of the most fascinating figures of Hindi cinema. But though the major events of his life are well known, if you were to ask, ‘what was he like?’ you would have no clear answer. There are several tantalising missing pieces in his story, impeding a full understanding of the man. Born in 1892 in an affluent family in Bengal, he was studying for the bar in London when he got involved in theatre – and later, in films – with Niranjan Pal, a playwright (and incidentally, freedom fighter Bipin Chandra Pal’s son). He also got involved with a pretty young German girl Mary Hainlin who was part of a theatre troupe called The Indian Players. “Remember, this was the Roaring Twenties,” says Peter. It was the time of flapper girls who wore their hair in short bobs and exposed their legs in knee-length skirts. It was the time of fading social inhibitions, and a creative outpouring in the worlds of art, dance, music, cinema.

He is the custodian of a priceless Bombay Talkies archive which throws valuable light on the studio in its golden years.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Himanshu and Mary fell in love. Filmmaker Cary Rajinder Sawhney, in an essay on Devika Rani in a book on superstars of Indian cinema, says that Himanshu “had a reputation as a… ladies’ man.” And journalist Rafique Baghdadi, in his book, Talking Films, notes: “Friends close to him [Himanshu Rai] called him the worst womaniser,” though they admitted that “from the day he started Bombay Talkies [in 1934], he never looked at another woman.”

Himanshu and Mary got married, went to Germany and, according to Peter, it was Mary who introduced Himanshu to UFA, a leading German film production company, where he met renowned German directors such as GW Pabst and Fritz Lang. This was probably the start of Himanshu’s long association with German directors and technicians over the years – such as Franz Osten who directed 16 films for Bombay Talkies or Joseph Wirsching who was the cameraman for many of them.

The ladies’ man

But according to Amrit Gangar, author of a book ‘Franz Osten and the Bombay Talkies: A Journey from Munich to Malad,’ “The assumption that Mary Hainlin introduced Himanshu Rai to the Germans and to UFA Studios needs to be examined and established.” He says that Niranjan Pal and Himanshu were already in contact with the Osten brothers – Franz, Peter and Ottmar

While the origins of Himanshu’s contacts with German film studios, directors and technicians might need more research, what is certain is that an important personal event occurred in Himanshu’s life in 1926 – Mary gave birth to a baby girl, Nilima.

But in a fateful twist, in 1929, Himanshu met someone else – the beautiful and glamorous Devika Rani, the grandniece of Rabindranath Tagore, and the daughter of the first Surgeon-General of Madras. She had gone to school in England, and was working for a London art studio. She was staying with Niranjan Pal and his English wife. Himanshu met her at a party. Bowled over by her beauty and talent, he offered her a job in his film, ‘Throw of Dice.’ For Devika Rani, Himanshu – more than ten years older than her – was a larger-than-life figure, already the star of the 1925 silent film ‘Light of Asia’ where he had played the Buddha. He became like her mentor. Cary Rajinder Sawhney writes that Himanshu had told Niranjan Pal about his German marriage, but had sworn him to secrecy. So maybe Devika Rani didn’t know about Himanshu’s secret marriage. Or did she? No one knows.

Abandoning Mary and their little daughter, Himanshu married Devika Rani in 1929 and went back to India with her; in 1934, they would go on to open a historic chapter of Hindi cinema by starting Bombay Talkies in Malad, then a distant, quiet suburb of Bombay. Why did he forsake his young German wife? “If you’ve ever looked at any pictures of Devika Rani, you’d know why he fell in love with her,” counters Peter simply. “Indeed, the two women knew each other and were friends. There are photographs of them together.”

When Nilima grew up, she married a German, Ernest Dietze in 1947 and migrated to Australia in 1952. Those were the days of the “White Only” immigration policy in that country (you couldn’t have more than 25 per cent of another race) and Nilima hid the fact that she had an Indian father. Also, maybe she didn’t want to have anything to do with the man who had left her when she was just a child. She never told her three sons (Peter has two brothers Walter and Paul) about him – till Peter discovered the picture in the attic. Once Peter found out though, he did all he could to track his Indian ancestry.

Ashok Kumar and Devika Rani became a hit pair and acted in many films, including the successful Vachan (above), 1938. Kumar was a lab technician at Bombay Talkies when Rai turned him into a hero. Devika Rani had eloped with her co-star Najamul Hussain and though she returned, Himanshu replaced Najamul with Ashok Kumar.

The death of Himanshu Rai

Bombay Talkies established itself as one of the leading film studios – it had a staff of 400 people, state-of-the-art equipment, and churned out films every year (many of which became big hits and are now regarded as classics). Devika Rani was the leading lady in many of them and the studio also introduced new stars such as Ashok Kumar. But running Bombay Talkies took its toll on Himanshu Rai. He had a nervous breakdown, was hospitalised and died in 1940. He was just 48. “He was pedalling very hard,” says Peter. “It was the story of a man struggling to keep his studio together.” The Second World War had begun and Himanshu’s lead director Franz Osten and the other Germans in Bombay Talkies were interned in camps in India. He had had a serious fallout with his long-time screenwriter Niranjan Pal. By this time there had also been a painful rift with Devika Rani. Some years ago, she had run away to Calcutta with a handsome young co-star Najamul Hussain (who came from an aristocratic Lucknow family), while they were shooting for a film called Jeevan Naiyya.

Himanshu persuaded Devika Rani to come back, but could things have been the same again? Indeed, Cary Rajinder Sawhney writes that many people blamed Devika Rani for her husband’s death.

After Himanshu’s demise Devika Rani took over Bombay Talkies but it was tough going. It was rare for a woman then – or even now for that matter – to run a studio. There were many problems, not least of them opposition from other powerful stakeholders in the company such as Sashadhar Mukherjee. In 1945, she quit the studio, married Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich (son of famous painter Nicholas Roerich) and went on to live a quiet life with him, first in Manali and then in Bangalore. But she took with her the entire Bombay Talkies archive. When she found she couldn’t take care of the material, she sent it to the New York Nicholas Roerich Museum. She died without any heir in 1994.

In 2001, Peter happened to be in New York and went to the Roerich museum. He got talking with the curator who showed him the Bombay Talkies archive.

Peter has organised a major exhibition based on the archive in Melbourne. He hopes to travel with the exhibition all over the world, including India.

When he came to know that Peter was actually Himanshu Rai’s grandson, he turned over the archive to him. Peter pored over the treasure trove: “You can picture vignettes of that time… even the receipt of the bottle of wine Himanshu ordered in Germany, the cup of coffee he drank,” he says.

In 2006 Peter paid a visit to Mumbai, and went with film historian Amrit Gangar to look at the dilapidated remains of the Bombay Talkies studio in Malad. And around three years ago he went to Udaipur palace, one of the locations for ‘Throw of Dice.’ “I literally walked in my grandfather’s footsteps,” says Peter. “It was a very moving experience. I recognised a chair in the museum that was in the film! It’s sad, everyone in Udaipur knows that Octopussy was shot there, but no one knows about real history, about ‘Throw of Dice’ and how the king at that time loaned Himanshu horses, elephants, costumes, furniture for the film.”

In 2006 Peter paid a visit to Mumbai, and went with film historian Amrit Gangar to look at the dilapidated remains of the Bombay Talkies studio in Malad. And around three years ago he went to Udaipur palace, one of the locations for ‘Throw of Dice.’ “I literally walked in my grandfather’s footsteps,” says Peter. “It was a very moving experience. I recognised a chair in the museum that was in the film! It’s sad, everyone in Udaipur knows that Octopussy was shot there, but no one knows about real history, about ‘Throw of Dice’ and how the king at that time loaned Himanshu horses, elephants, costumes, furniture for the film.”

Today it is Peter’s mission to make sure his grandfather’s legacy is not forgotten. “It is my destiny. It’s time for Himanshu to have his moment in the sun,” he says. And time perhaps to put together the little-known but mesmerising personal story of Himanshu Rai, Mary Hainlin and Devika Rani.