For the Japanese in World War II, surrender was unthinkable. So unthinkable that many soldiers continued to fight even after the island nation eventually did surrender.

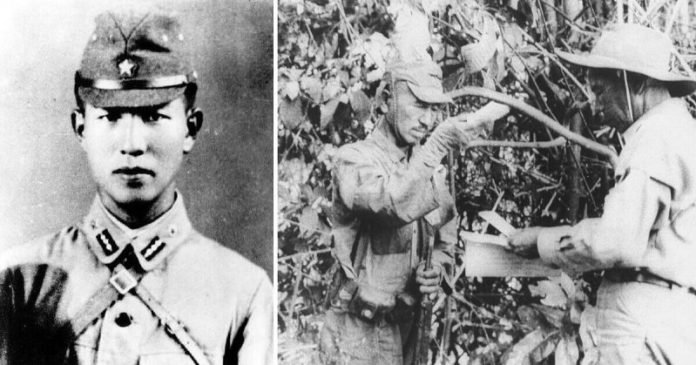

The idyllic islands of the Pacific Ocean typically have little role to play in the wider world aside from offering white shores and blue oceans that come about as close to paradise as it gets. But in World War II, these islands were bloodily contested. They represented strategic positions for the Allies, who could establish bases for bombing raids on the then-Axis Japan. In turn, Japanese soldiers were sent to these islands to defend them at all costs. Many, including a lieutenant named Hiroo Onada, were instructed to fight until killed; surrender was not an option. Hiroo Onada and others obeyed these orders literally. In fact, Onada continued to fight for 29 years after World War II ended.

Twentieth-century Japan had transformed the ancient concept of Bushido — a military code of conduct presented in some texts as “a way of dying” that demanded samurai be prepared to lay their life down for their lords — into a full-on propaganda tool to stir up nationalism and a culture of death before surrender. Surrender was so anathema to World War II Japan that Emperor Hirohito’s surrender speech did not even feature the word “surrender.” Instead, he characterized the coming capitulation as “enduring the unendurable and suffering the unsufferable.”

This attitude led Lieutenant Onada and his men to go into hiding on the mountains of Lubang Island in the Philippines after Allied forces took the island back from Japanese control in February of 1945. Major Yoshimi Taniguchi was evacuating the island with other Japanese soldiers but instructed Onada and other men to stay and fight. “It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens we’ll come back for you,” the major said. “As an intelligence officer,” said Onada, “I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die. I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier.” The war ended in September of that year, but Onada continued to follow his orders.

During his time in the jungle, Onada engaged in guerilla warfare and several skirmishes with the local Filipinos and police. In October of 1945, he and his team found a leaflet that a villager had left. It read: “The war ended on August 15. Come down from the mountains!” Later that year, more leaflets came, but Onada and his men believed them to be American propaganda. They were full of mistakes, he said, and so they could not have come from the Japanese. And how could the Japanese have surrendered, anyway? So, they stayed in the jungle for 29 years.

Japan’s involvement in WWII came to a halt shortly after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Onoda belonged to the family lineage of an ancient Samurai warrior class, a class fiercely reputed for unwavering loyalty and honour to the flag they represent. He trained in the commando class and was deployed to Lubang Island in the Philippines on December 26, 1944.

His orders from his superiors were clear:

“You are absolutely forbidden to die by your own hand. It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens, we’ll come back for you. Until then, so long as you have one soldier, you are to continue to lead him.”

Lubang Island was taken by the Allies a few months after Onoda’s deployment, and most of the Japanese guerrillas there were either captured or killed. Onoda with three other surviving soldiers took to the hills.

During one of the village raids on October 1945, Onoda and his men had found a leaflet left by the islanders which read: “The war ended on August 15. Come down from the mountains!” They all agreed that it was probably a trap.

On September 1949, Private First Class Yuichi Akatsu left the group to live on his own in the jungles for six months before surrendering to the Philippine Army who had accepted his surrender and treated him well. In 1950, Akatsu left a note describing this hospitality and in the jungle. Onoda and his men found the note but concluded that Akatsu was conspiring with the enemy.

Onoda and two of his remaining men carried out guerrilla activities against the villages at the foothills, sabotaging food supplies, and having gunfights with locals. They survived on a diet of bananas supplemented with coconuts and other fruits. For meat, they hunted wild boars, caribou, chickens and iguanas and killed cows of the local farmers.

“Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer, I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die.”

– Hiroo Onoda

In June 1953, Corporal Shoichi Shimada, who was one of the men in Onoda’s group, was shot in the leg during a shoot-out with some fishermen. He was nursed back to health, but died on May 7, 1954, when he was killed instantly by a bullet fired by a search party.

Over time, planes flew overhead dropping leaflets, news clippings, photographs and letters from the soldiers’ families, including the surrender order by General Yamashita himself. Efforts also included former Japanese soldiers travelling into the area with loudspeakers, insisting that the war was over.

Once again, they suspected this was all a ruse by the Allied forces to trick them into surrendering.

As part of their military assignment to disrupt the operations of the enemies, they would burn piles of rice that the farmers had gathered. On October 19, 1972, Kozuka, the last soldier with Onoda, was shot through the heart by local police while engaging in this activity.

Onoda was now alone.

In 1974, a Japanese university dropout named Norio Suzuki had gone to Lubang with the express mission of finding Onoda. He eventually did. Suzuki had explained to Onoda that the war has ended but Onoda explained that he could not surrender without the explicit order of his commander.

Suzuki went back to Japan and requested the aid of the Japanese Government to track Onoda’s former commander, Major Taniguchi, who had since become a civilian and was now working in a bookstore.

On March 9th, 1974, Major Taniguchi was flown to Lubang Island where, after 29 years of abandonment, personally ordered Onoda to stand down.

A tired Onoda, who turned 52, walked from the jungle in full-dress uniform on March 10, 1974. He surrendered his sword to Major General J. L. Rancudo of the Philippine Air Force who immediately returned it to Onoda as a mark of respect.

The ceremony was repeated for the world press with the president of The Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, who pardoned him for his three decades of crimes due to the circumstances of Onoda believing that the war was ongoing.

Onoda and his men killed about thirty Lubang Islanders while foraging for food, and wounded approximately one hundred more.

At the time of his surrender, he had his sword, a functioning rifle with 500 rounds of ammunition, and several hand grenades. He also had the dagger his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself with if he was ever captured.

Onoda returned to a drastically different Japan. He was much troubled by what he saw as the withering of traditional Japanese values.

He left for Brazil a year later on April 25, 1975, to raise cattle, an interest he acquired when he was listening to Australian cattle shows on his stolen transistor radio during his years in the jungle.

In 1984, Onoda once again went back to Japan to establish an educational camp for the young, after reading about a Japanese teenager who had murdered his parents in 1980.

He returned to Lubang Island in 1996 to donate $10,000 to local schools. Many think of him as part of their local history, and officials from the Philippines sent their condolences when he passed away in 2014 due to heart failure in Tokyo.

“Men should never give up. I never do. I would hate to lose.”

– Hiroo Onoda

Did you know? Hiroo Onoda was not the last Japanese soldier to surrender. Private Teruo Nakamura, was the last known Japanese holdout, surrending several months after Onoda, on December 18, 1974 when he was discovered by the Indonesian Air Force Morotai Island, in one of Indonesia’s nothernmost islands. Mr Nakamura was repatriated and died in 1979.

It was also rumoured that a captain named Fumio Nakaharu might still be holding out at Mount Halcon in the Philippines. A search team headed by his former comrade-in-arms had found what they believe to be his hut. Unfortunately, no evidence that Nakaharu lived as late as 1980 has been documented.

The most recent case of Japanese holdouts was in 2005, where two former soldiers from the Panther division of the Japan’s Imperial Army, was discovered on Mindanao Island in the Philippines. The men are Yoshio Yamakawa 87, and Tsuzuki Nakauchi, 85 and although they knew of Japan’s defeat, they did not surrender themselves as they were afraid of getting court-martialed if they returned home.